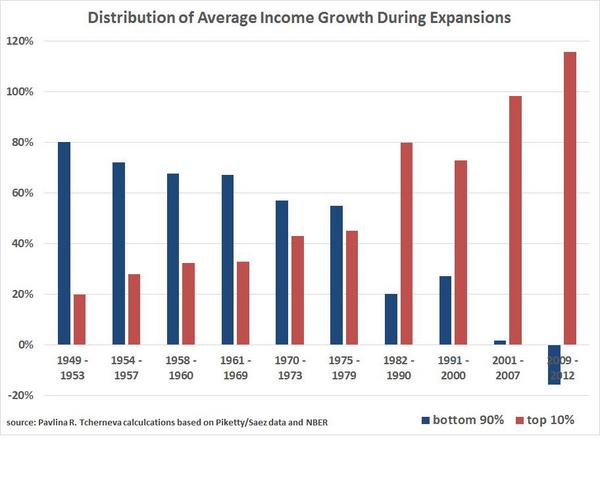

Chart of the day

September 24, 2014 Leave a comment

Wow. From here.

Politics, health care, science, education, and pretty much anything I find interesting

September 24, 2014 Leave a comment

Jon Stewart on Republicans in Congress and climate change. Awesome.

September 24, 2014 1 Comment

From a Big Picture gallery of flooding in India:

An aerial view taken from an Indian Air Force helicopter shows the flooded Srinagar city, Sept. 11. (Adnan Abidi/Reuters)

September 24, 2014 Leave a comment

There’s been a lot written about how Republicans have turned their utopia of conservative policy-making in Kansas into a dystopia, but I haven’t linked to any of it yet. Chait with the best take (while also slapping down Thomas Frank yet again) I’ve yet seen:

The cause of all the trouble for the Republicans is Brownback. Sam Brownback is not some random shmoe who stumbled onto the party ticket and proceeded to say something offensive about rape or evolution. Brownback comes from deep within the party bosom, first as a prominent member of the revolutionary House Republican class of ’94, then senator (he hired Paul Ryan as his legislative director), and since 2011, governor.

He has centered his governorship on a plan to phase out the state’s income taxes. Over and over, Brownback held up Kansas as a proving ground for the proposition that cutting taxes for the affluent would unleash prosperity. Opponents warned the plan would wreak havoc on the state budget; Brownback and his supporters, including influential national Republican policy-makers like Arthur Laffer and Stephen Moore, insisted no such thing could happen…

Brownback’s program has failed every practical test. The state budget is hemorrhaging revenue, even after making up some of the funds lost on tax cuts for the affluent by jacking up taxes on the poor. Since Brownback’s cuts took effect, job growth in Kansas has lagged behind the national level and behind all but one of its neighboring states…

Brownback’s biggest mistake was to forget a lesson Frank made well: Even in Kansas, tea-party populism requires the maintenance of a ruse. One needs cultural elites and other enemies to bash in broad daylight while doing the dark work of plutocracy behind the scenes. Openly conducting class warfare on behalf of the rich is no way for a pseudo populist to get ahead. [emphasis mine]

September 24, 2014 5 Comments

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised, but I was a little taken aback by this latest Pew result as shared in Wonkblog:

2. A majority of Republicans say politicians aren’t talking enough about faith. Pew Research Center

Pew Research CenterFifty-three percent of Republicans say that political leaders are talking too little about their faith, compared to less than a third of Democrats. Again, while Democrats have remained consistent on this measure since 2010, Republicans have shifted nearly 10 percentage points.

Politicians in America not talking enough about religion? Yeah, that’s a problem.

September 24, 2014 Leave a comment

Many years ago I realized that the biggest impediment to me being an effective college teacher was my need/compulsion to get through a certain fixed amount of material on any given topic and within the course as a whole. My great epiphany was realizing how very little of the information I was conveying to my students would have any lasting value to them beyond my final exam. Since that time I have tried to cut and cut content in order to leave more class time to focus on critical thinking– something I hope my students will benefit from long, long after my class is over. I know there’s still too much content that I feel they just “have to know” even though they really don’t, but I’m a lot better. In my meetings with our new graduate student teachers I came to call this compulsion to cover too much material the “tyranny of content.” I’ve been pretty proud of that term and use it a lot. In a recent conversation with a colleague suffering from this tyranny I actually did a google search and discovered that I’m not so original. Turns out another academic has already beaten me to blogging about the term and that we both basically mean the same thing, but this goes into some nice detail and I heartily endorse what he has to say:

I have colleagues who complain about how full their modules are, how they can’t do anything different than straight lecture or they won’t cover the material, feel overwhelmed by new material that needs to be incorporated because there is just so much old material that the students need to know. I call this the tyranny of content.

In HE, we decide the content. As professionals and experts in our respective fields, we decide what is important and what is not. We put together a syllabus, we assemble the learning objectives and declare the learning outcomes. We decide the content. If someone else is doing that for us, we become trainers rather than professionals.

Given the amount of information that is available to teach, we can never hope to design a programme that would cover it all. So why are we trying so hard to do just that?

We need to remember that the ‘H’ in Higher Education stands for higher order skills (critical thinking, critical analysis, synthesis etc.). How can cramming more stuff into a syllabus help students gain higher order thinking skills? I know that there are a few enlightened lecturers out there who focus on the higher order skills, but most of the faculty at HE institutions are focused on stuff.

There are simple reasons why this has happened. Stuff is easier to teach and assess. Stuff is what the students demand – they want a drip feed of facts that they can spew forth on demand. Stuff easily fits into the measurable metrics administrators demand. Stuff rules! We are slaves to the tyranny of content.

Higher order skills are incredibly difficult to teach (or can be)…

I every field of knowledge there is expertise. An expert knows a lot of stuff, but more importantly, they approach problems both within and outside of their area of expertise in a different way than a novice would. It is how they look at the problem, how they approach the problem, how they organise the problem that confirms to you that they are an expert in some related field. This critical examination of the problem, the organisation of the information, and then careful approach to addressing the problem is what we really need our students to learn. It is how we study the problem, not the problem itself that is important, and yet, we focus, almost exclusively, on the information around the problem, the right answer, the solution.

We need to somehow rethink what we do in HE so that we can shake off the tyranny of content. Our students have access to as much information as we have, and yet we often insist on repackaging and presenting it in our our own image. We need to refocus on the higher part of higher education.

Recent Comments