Quick hits (part I)

May 18, 2024 Leave a comment

1) Man, it was interesting to read how crazy the “student-centered teaching” crowd has gotten. Chronicle of Higher Ed:

The problem comes when advocates of teaching reform cast judgment on prosaic, everyday classroom practices — such as lectures and multiple-choice exams — that aren’t necessarily damaging and can, in fact, be legitimate pedagogical choices. Try Googling “high-stakes exams”: Littered among the search results are phrases like “dangerous consequences” and “psychological toll.” In a conference talk I once saw high-stakes exams included in a list of possible traumatic experiences. As educational developers, we need to respect instructor autonomy and avoid reproach. After all, the degree to which you are authentic, caring, and invested in student success tends to matter more than which gadgets you choose from the teaching toolkit.

2) Thomas Mills on the NC Republicans new mask ban, “The party of stupid”

Republicans, though, are trying to bastardize the anti-mask law that was suspended during CIVID. They claim they are just trying to return to normal in the post-pandemic era. In reality, they are virtue-signaling to their base and pandering to stupidity.

Republicans refuse to allow an exception to the law for health reasons. They don’t have a good reason. They just want to stick it to woke liberals. In their view, masks are a symbol of the fake pandemic…

The bill is really a reactionary response to the mask mandates imposed during the height of COVID. Republicans spent the pandemic in denial about COVID’s severity and pushed back against government regulations meant to curb its spread. They politicized the pandemic and paid a serious price. According an NPR study, “…[P]eople in counties that voted strongly for Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election were ‘nearly three times as likely to die from COVID-19’ as people in pro-Biden counties.” The bill Republicans are pushing through the legislature right now is the epitome of wearing your stupidity on your sleeve.

They also don’t see the irony in their bill. Passing a law that prevents wearing masks is every bit as heavy-handed as imposing mask requirements. Both measures are examples of government limiting our freedoms. The bill is just another example of Big Government conservatism.

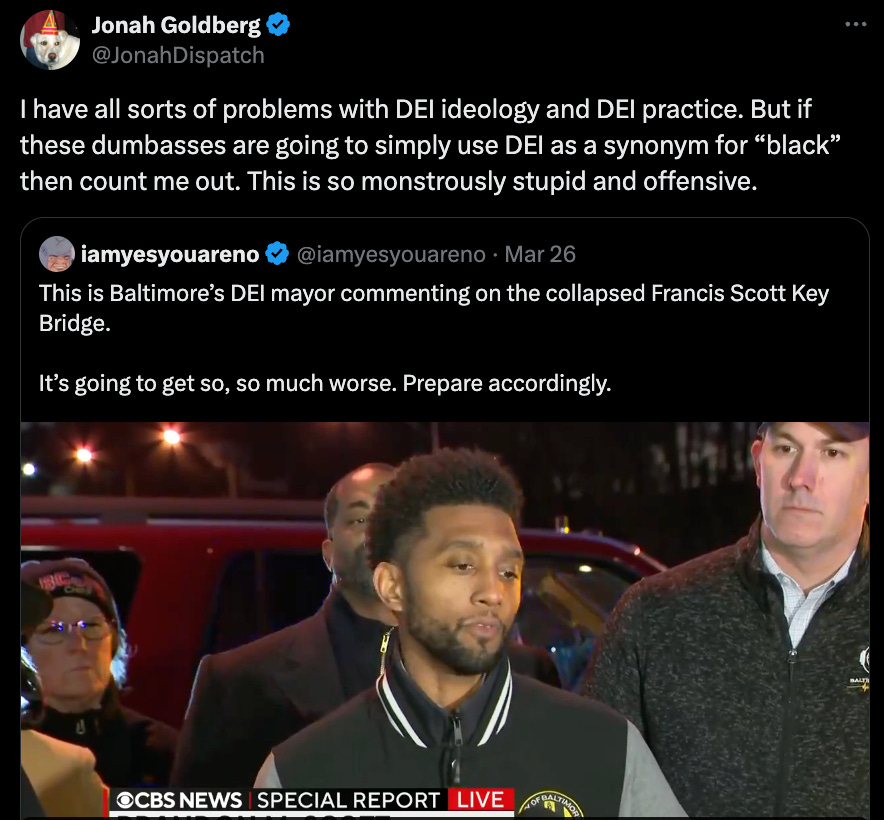

3) I don’t buy this for a second, “How DEI helped Davidson College choose the name of its new athletic field. ” Davidson College so did not need a DEI office to realize that they would have a problem in trying to name a field after former football coach, David Fagg.

4) This was fantastic. Gift link, “Why Do People Make Music? In a new study, researchers found universal features of songs across many cultures, suggesting that music evolved in our distant ancestors.”

That debate continues to this day. Some researchers are developing new evolutionary explanations for music. Others maintain that music is a cultural invention, like writing, that did not need natural selection to come into existence.

In recent years, scientists have investigated these ideas with big data. They have analyzed the acoustic properties of thousands of songs recorded in dozens of cultures. On Wednesday, a team of 75 researchers published a more personal investigation of music. For the study, all of the researchers sang songs from their own cultures.

The team, which comprised musicologists, psychologists, linguists, evolutionary biologists and professional musicians, recorded songs in 55 languages, including Arabic, Balinese, Basque, Cherokee, Maori, Ukrainian and Yoruba. Across cultures, the researchers found, songs share certain features not found in speech, suggesting that Darwin might have been right: Despite its diversity today, music might have evolved in our distant ancestors.

5) And it got me curious about the pentatonic scale. This 15 year old video with Bobby McFerrin is terrific.

6) Eric Levitz is not a great fit at Vox, but, I guess that means, good for Vox. This was good, “Make “free speech” a progressive rallying cry again: Protecting radical dissent requires tolerating right-wing speech.”

Attempts to sanction academics for speech increased dramatically over the past 10 years, according to a 2023 report from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE). Conservative activists were responsible for 41 percent of these campaigns, but a majority came from the left. In national discourse during this period, meanwhile, conservatives often espoused a support for free speech, while some progressives forthrightly defended restricting free expression on college campuses.

In recent months, however, social justice advocates have been forced to contest the very ideas about speech and inclusion that they had once popularized.

Since the onset of the Israel-Hamas war and the resulting surge of pro-Palestinian activism at American colleges, the campus free speech debate has inverted. Now, it is Republican politicians who insist that college administrators must discern the bigotry implicit in non-hateful speech (such as the chant, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free”) and then silence that speech to protect a historically oppressed minority group on campus.

And they have enjoyed some success. In recent months, several colleges have disciplined pro-Palestinian activists for ordinary speech acts and mobilized force against their acts of civil disobedience. Congress, meanwhile, is on the verge of enacting a law that would empower the federal government to suppress anti-Zionist advocacy on college campuses.

Progressives have lamented such attempts to regulate campus speech as authoritarian attacks on academic freedom. In their estimation, the aggressive policing of free expression at US colleges since October 7 has not served the interests of the marginalized, but rather it has abetted the mass murder of a disempowered people.

All of which raises a question: In light of these developments, should students concerned with social justice rethink their previous skepticism of free speech norms, for the sake of better protecting radical dissent?

I think the answer is yes.

7) Nice headline from Ian Milhiser. Appalling that Alito (what a hack!!!) and Gorsuch dissented. “The Supreme Court decides not to trigger a second Great Depression”

The Supreme Court delivered a firm and unambiguous rebuke to some of America’s most reckless judges on Thursday, ruling those judges were wrong to declare an entire federal agency unconstitutional in a decision that threatened to trigger a second Great Depression.

In a sensible world, no judge would have taken the plaintiffs arguments in CFPB v. Community Financial Services Association seriously. Briefly, they claimed that the Constitution limits Congress’s ability to enact “perpetual funding,” meaning that the legislation funding a particular federal program does not sunset after a certain period of time.

The implications of this entirely made-up theory of the Constitution are breathtaking. As Justice Elena Kagan points out in a concurring opinion in the CFPB case, “spending that does not require periodic appropriations (whether annual or longer) accounted for nearly two-thirds of the federal budget” — and that includes popular programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Nevertheless, a panel of three Trump judges on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit — a court dominated by reactionaries who often hand down decisions that offend even the current, very conservative Supreme Court — bought the CFPB plaintiffs’ novel theory and used it to declare the entire Consumer Financial Protection Bureau unconstitutional.

In fairness, the Fifth Circuit’s decision would not have invalidated Social Security or Medicare, but that’s because the Fifth Circuit made up some novel limits to contain its unprecedented interpretation of the Constitution. And the Fifth Circuit’s attack on the CFPB still would have had catastrophic consequences for the global economy had it actually been affirmed by the justices.

8) Sarah Stillman has a great history of telling stories of how our criminal justice system immorally screws people over for money. This is as damning as any.

Le’Essa Hill, aged eighteen, works at a Subway sandwich shop near Flint, Michigan. Her younger sister, a fifteen-year-old aspiring zookeeper named Addy, helps run a “mini-farm” inside the family’s green clapboard house. When I first met the girls, early this year, Addy was caring for five dogs, four cats, two rabbits, and a lizard named Lily, who ate crickets and kale. Le’Essa and Addy were unlikely candidates to wage an ideological battle against two big private-equity firms, but they were in the midst of one because of a situation involving their father, Adam Hill. For more than a year, while Adam was held in the county jail, awaiting trial, the girls had been prevented from seeing him in person.

“My dad is the kind of guy who can climb a tree even if it doesn’t have any branches,” Le’Essa told me. “He just wraps his legs around the trunk.” Le’Essa’s parents separated when she was young, and her dad has struggled with addiction. “He can be really silly and childish, but in a good way,” she added. “Like when something goes wrong, he’ll make up a funny song about it.” Le’Essa, who, like many teen-agers, has experienced mental-health struggles, wished that she had Adam’s companionship. “I feel like my perception of other people is often completely wrong, and I get slapped in the face by that reality a lot,” she told me. “My dad is the only person who really gets it, and so if I could have deeper conversations with him that would be magical.

A few years later, the county went after an even steeper commission. In the sheriff’s office, a captain named Jason Gould helped negotiate a deal with a Securus competitor called Global Tel*Link (or GTL, now known as ViaPath), which included a fixed commission of a hundred and eighty thousand dollars a year, plus a sixty-thousand-dollar annual “technology grant,” and twenty per cent of the revenue from video calls. The jail chose not to restore families’ access to in-person visits. To celebrate the deal, an undersheriff joked to Gould, by e-mail, “You are not Captain Gold for nothing!”

County sheriffs across the country were making similar deals with Securus and GTL, which resulted in millions of dollars in commissions. Many of those counties replaced in-person visits with the companies’ video calls.

9) I didn’t realize the Simpsons had forced Harry Shearer to stop voicing any non-white characters at the height of the woke moral panic in 2020.

“Folk say the show has become woke in recent years and one of my characters has been affected,” Shearer said. “I voiced the Black physician, Dr. Hibbert, who I based on Bill Cosby. Back then he was known as the ‘whitest Black man on television.’ Then, a couple of years ago, I received an email saying they’d employed a Black actor, who then copied my voice. The result is a Black man imitating a white man imitating the whitest Black man on TV.”…

“The Simpsons” creator Matt Groening told USA Today in 2021 that it “was not my idea” to have white actors stop voicing characters of color, “but I’m fine with it. Who can be against diversity? So it’s great.”

“However, I will just say that the actors were not hired to play specific characters,” he added at the time. “They were hired to do whatever characters we thought of. To me, the amazing thing is seeing all our brilliant actors who can do multiple voices, do multiple voices.”

10) Jerry Seinfeld made big news giving the commencement speech at my alma mater because a few dozen people walked out (to their credit, they did not attempt any further disruption). The speech is quite good. That said, as much as I appreciate Conor Friedersdorf’s take (“Jerry Seinfeld’s Speech Was the Real News: Why did the media focus less on his words and more on the 30 protesters who didn’t hear them?”), the speech wasn’t that good. It’s not like commencement speeches make news typically (excepting the recent disaster at Ohio State).

11) Rather distressing, “How One Crack in the Line Opened a Path for the Russians“

Ukraine is more vulnerable than at any time since the first harrowing weeks of the 2022 invasion, Ukrainian soldiers and commanders from a range of brigades interviewed in recent weeks said. Russia is trying to exploit this window of opportunity, stepping up its assaults across the east and now threatening to open a new front by attacking Ukrainian positions along the northern border outside the city of Kharkiv.

Months of delays in American assistance, a spiraling number of casualties and severe shortages of ammunition have taken a deep toll, evident in the exhausted expressions and weary voices of soldiers engaged in daily combat.

12) Can I just say– ugggg, contemporary Sociology– to this? “Did Kids Become More Racist Under Trump? A new book examines the white children who felt emboldened to be openly bigoted while he was president.”

Between 2017 and 2019, Hagerman, who is on the faculty at Mississippi State University in Starkville, and two Ph.D. students conducted 45 interviews with children ages 10 to 13. All the subjects lived in two politically “purple” towns — one in Massachusetts, the other in Mississippi. Both towns were evenly split between registered Democrats and Republicans, and both had a significant white population living near people of color. It wasn’t Hagerman’s first time interviewing kids this age. From 2011 to 2012, when Barack Obama was president, Hagerman spent two years with the families of 36 white children, also middle-schoolers, in a midwestern city. “I babysat their kids, I interviewed the parents and children, I spent a lot of time observing them with their friends,” she explains. Back then, every white child she interviewed, regardless of their family’s political affiliation, told her racism was “bad” and a serious problem. Some kids didn’t even want to talk to Hagerman about race because they were scared she would think they were racist. “That’s quite different from the white kids in this new study,” Hagerman told me. The study participants’ answers revealed feelings that divided them into three distinct groups but not along the lines one might expect, like Northeast versus Deep South or younger versus older. Rather, the groups were anti-Trump white kids, anti-Trump children of color, and pro-Trump white kids. Cammie turned out to be just one of many in that last cohort who were unbothered by Trump’s overtly racist statements.

I’d love to see what a political science journal would have to say about me submitting something based on 45 interviews with a non-random assortment of people.

Because, maybe they did! But, I’m sure not going to accept that conclusion from this.

13) Lots of good stuff here from Yglesias, “What the right gets right”

The brutality of history

Progressives typically characterize their stance on this as being that it’s important to tell people about the darker aspects of history. And they’re right — it is a good idea for people to learn about those things. But I think the standard progressive read of this gets the figure and the ground backwards. The implication of a lot of these takes on episodes of violence, bigotry, displacement, and cruelty in American history is that these episodes are what’s distinctive about the United States of America.

But if you read the history of anywhere, you’ll see that it’s not like there’s some other country where you wouldn’t say “it’s important for people to learn about the darker aspects of our history.” History is dark! In the winter of 1069-70, William the Conquer and his fellow Normans put down a rebellion in northern England by burning rebellious villages and deliberately destroying food stockpiles, inducing famine and mass death.

Here’s the introduction of historian Ivo Schoffer’s article “The second serfdom in Eastern Europe as a problem of historical explanation:”

“While the German peasant is driven afield to gather snails and wild strawberries for his lord, is plundered and harried and tortured without hope of redress, his English brother is a member of a society in which there is, nominally at least, one law for all men.” With this remark, Tawney proceeds to describe and explain the process of commutation in sixteenth century England. It is proposed here to tackle this problem in its reverse form at the other end of Europe. Why had the German peasant — or for that matter, why had the peasant in Eastern Europe — lost his social position? Why could he be “plundered and harried and tortured?” By the sixteenth century serford had virtually disappeared in England, the Low Countries, Scandinavia, Switzerland, Italy and Spain and was well on the way to disappearance in Western Germany and France. On the other side of the Elbe — in Silesia, Eastern Germany, Poland, Livonia and Lithuania — serfdom had become a firm institution, spread over the whole of the vast agrarian area.

The snail thing is a reference to one of the grievances that led to the German Peasants’ Revolt of 1524-25, which was brutally suppressed in a way that led to the slaughter of maybe 100,000 peasants.

The First and Second Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 had two distinct phases. In the first, Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria teamed up against the Ottoman Empire. In the second, Bulgaria fought against its former allies. In the end, “Bulgarian, Serbian, Greek, and Ottoman forces committed mutual acts of violence including large-scale destruction and arson of villages, beatings and torture, forced conversions and indiscriminate mass killing of enemy non-combatants.”

Those are just a few things I’ve read about recently, along with the Bronze Age Collapse.

Conservatives have their own flawed tendency to lapse into nostalgia for the recent past, but I do think they typically have a more clear-eyed view of the reality that the whole of human history is littered with atrocity and cruelty. It’s naive to view our sociocultural antecedents here in the United States as flawless, shining heroes, but it’s also naive to think the violence and brutality of American history is what’s unique about it, rather than the fact that we’ve settled into a prosperous and liberal status quo.

The right side of history

Martin Luther King Jr.’s mantra, paraphrasing Theodore Parker, that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice” is a nice bit of motivational speaking. But this often leads progressives to the view that there is a strong and inherent directionality to history, and thus that any noisy movement for reform with adequate progressive branding must be good. You hear a lot with regard to the Gaza protests that the people complaining are just the same as the people who complained about every good and virtuous social movement of the past. Implicit is the sense that there is no such thing as a social movement that was bad.

But Communism, to cite probably the most important example, was really bad!

14) Yglesias also sent me to this 13 year old article which I love “Rebounding is a Mental Skill”

All of this suggests that rebounding is a skill. Yesterday Jonah Lehrer –– author of How We Decide (an excellent book on behavioral economics and decision-making) – posted Basketball and Jazz at wired.com. This post reviews research explaining the mental aspect of rebounding.

A few years ago, a team of Italian neuroscientists conducted a simple study on rebounding. At first glance, rebounding looks like a brute physical skill: The tallest guy (or the one with the highest vertical) should always end up with the ball. But this isn’t what happens. Instead, some of the best rebounders in the history of the NBA, such as Dennis Rodman and Charles Barkley, were several inches shorter than their competitors. What allowed these players to get to the ball first?

The rebounding experiment went like this: 10 basketball players, 10 coaches and 10 sportswriters, plus a group of complete basketball novices, watched video clips of a player attempting a free throw. (You can watch the videos here.) Not surprisingly, the professional athletes were far better at predicting whether or not the shot would go in. While they got it right more than two-thirds of the time, the non-playing experts (i.e., the coaches and writers) only got it right about 40 percent of the time. The athletes were also far quicker with their guesses, and were able to make accurate predictions about where the ball would end up before it was even airborne. (This suggests that the players were tracking the body movements of the shooter, and not simply making judgments based on the arc of the ball.) The coaches and writers, meanwhile, could only predict a make or miss after the shot, which required an additional 300 milliseconds.

What allowed the players to make such speedy judgments? By monitoring the brains and bodies of subjects as they watched free throws, the scientists were able to reveal something interesting about the best rebounders. It turned out that elite athletes, but not coaches and journalists, showed a sharp increase in activity in the motor cortex and their hand muscles in the crucial milliseconds before the ball was released. The scientists argue that this extra activity was due to a “covert simulation of the action,” as the athletes made a complicated series of calculations about the trajectory of the ball based on the form of the shooter. (Every NBA player, apparently, excels at unconscious trigonometry.) But here’s where things get fascinating: This increase in activity only occurred for missed shots. If the shot was going in, then their brains failed to get excited. Of course, this makes perfect sense: Why try to anticipate the bounce of a ball that can’t be rebounded? That’s a waste of mental energy.

The larger point is that even a simple skill like rebounding reflects an astonishing amount of cognitive labor. The reason we don’t notice this labor is because it happens so fast, in the fraction of a fraction of a second before the ball is released. And so we assume that rebounding is an uninteresting task, a physical act in a physical game. But it’s not, which is why the best rebounders aren’t just taller or more physical or better at boxing out – they’re also faster thinkers. This is what separates the Kevin Loves and Kevin Garnetts from everyone else on the court: They know where the ball will end up first.

Such research suggests that rebounding may not be a skill that is easy to teach. If some people can see where the ball might be going before the shooter even takes the shot, these players will always have the advantage in the rebounding game. And hence, the players with this mental skill will tend to be good rebounders (and those without the skill will not).

15) So true from Chait, “No, Your Pet Issue Is Not Making Biden Lose It’s inflation, not Israel or class warfare.”

he American political landscape in 2024 seems like a very simple story that people continue to overcomplicate. There was a large, global surge in prices in 2021 and 2022 as the economy restarted following the COVID-19 pandemic. That inflation surge left Joe Biden, like leaders in almost every major democracy, deeply unpopular. Biden, like his global peers, has yet to recover.

Is it possible that Biden’s standing can recover as the economy returns to health and the inflation surge recedes further into the past? Sure. But as every month goes by, that prospect gets a bit less likely, and it grows increasingly probable that we will look back and conclude that Biden’s defeat was preordained.

Numerous data points are converging on this explanation. The most recent New York Times polling again finds Biden trailing in all the swing states (except in Michigan, and only if you count likely voters as opposed to all registered voters). Those states find Democrats winning every Senate race.

The point here is that Democrats have a Joe Biden problem, not a partywide problem. Regular, mainstream Democratic candidates are holding up just fine in the purple states.

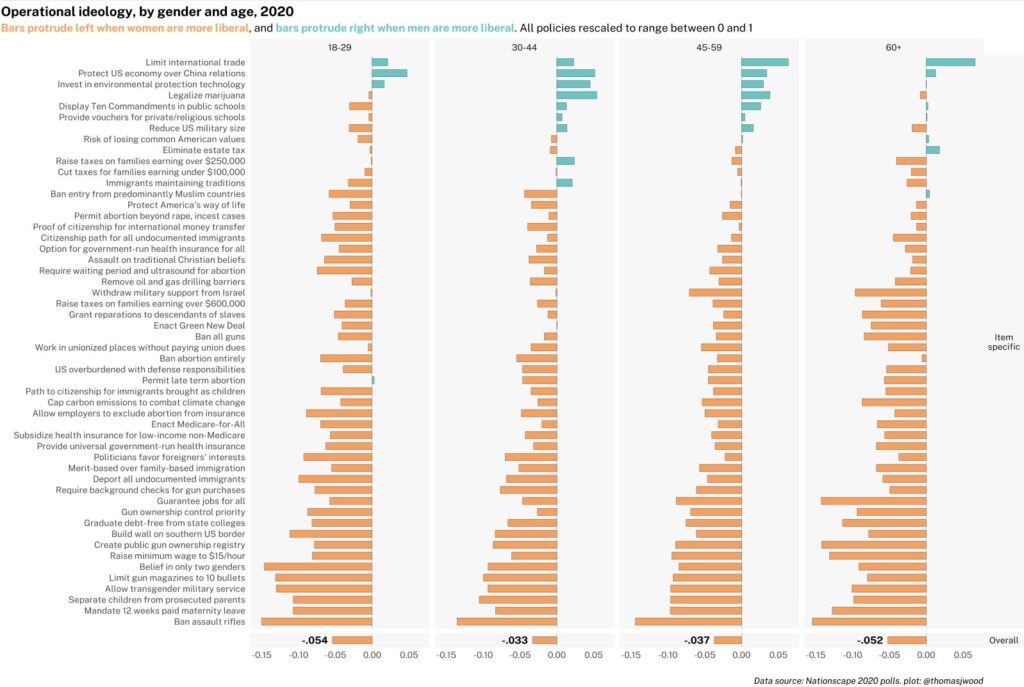

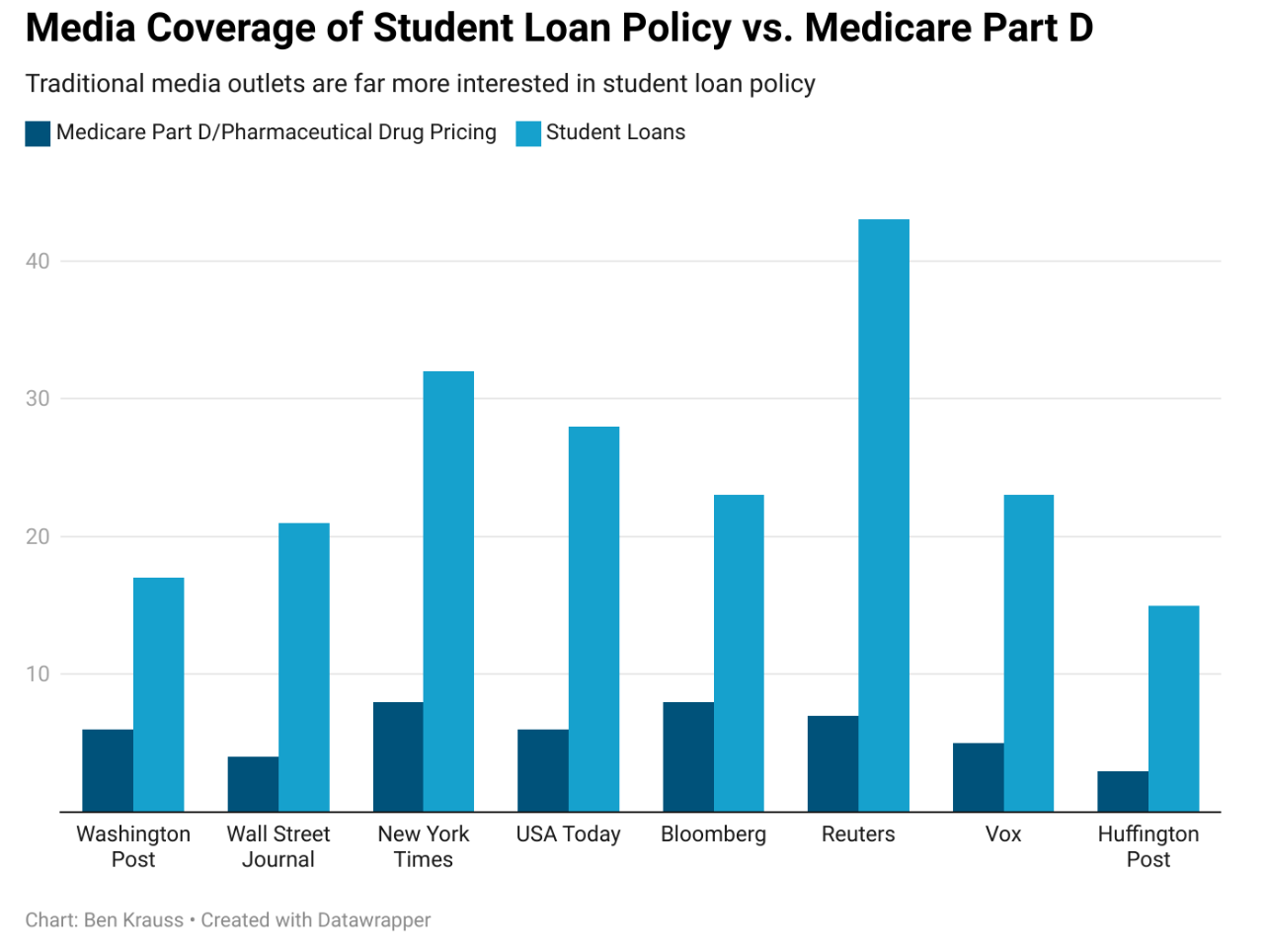

The story is being overcomplicated in the public’s mind in large part because various ax-grinders want to use Biden’s struggles to push the party toward their positions. Critics of Israel have fixated on the problems created by encampments at elite universities. And it is true that the news media’s intense coverage of an issue that splits the Democratic coalition and unites the Republican coalition hurts Biden and helps Trump.

But that does not accurately reflect the nature of Biden’s polling deficit. The Harvard youth poll found Israel-Palestine at the bottom of young voters’ concerns. Even polls of college students (who are a minority of young people) find low levels of concern about the issue.

The Times poll confirms this again. It finds that of those voters who supported Biden in 2020 but aren’t planning to support him in 2024, just 10 percent call foreign policy their most important issue and don’t sympathize with Israel over the Palestinians. Overall, the public continues to sympathize with Israel over the Palestinians by a margin of 41 percent to 22 percent…

Another, more traditional form of ax-grinding came recently from Mark Penn in a Times op-ed. Penn was a key strategist for Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign, during which he repeatedly insisted that Barack Obama was too left-wing to be elected president. Penn has since been sidelined from mainstream Democratic politics, and his polling was the basis for an unsuccessful scheme to run a “No Labels” centrist candidacy.

Penn’s long-standing fixation is that Democrats should move to the center across the board. Some of his beliefs about this are correct: The party has moved to the left of the electorate on immigration, climate, and many social issues.

But Penn has always been insistent that the Democrats’ biggest weakness is their desire to tax the rich, and he returns to this claim again in the Times.

“Instead of pivoting to the center when talking to 32 million people tuned in to his State of the Union address,” he writes, “Mr. Biden doubled down on his base strategy with hits like class warfare attacks on the rich and big corporations.”

In reality, taxing the rich and corporations is Biden’s most popular issue. One recent poll found that Biden’s plan to raise taxes on people making more than $400,000 a year commands support from 69 percent of registered voters. Nice. Even a majority of Republicans approve of the idea.

If Biden could get the electorate to focus on taxes, he would have a much more favorable environment. That isn’t easy. The campaign media is inherently averse to covering policy.

16) Some high quality social science, “The effects of Facebook and Instagram on the 2020 election: A deactivation experiment”

We study the effect of Facebook and Instagram access on political beliefs, attitudes, and behavior by randomizing a subset of 19,857 Facebook users and 15,585 Instagram users to deactivate their accounts for 6 wk before the 2020 U.S. election. We report four key findings. First, both Facebook and Instagram deactivation reduced an index of political participation (driven mainly by reduced participation online). Second, Facebook deactivation had no significant effect on an index of knowledge, but secondary analyses suggest that it reduced knowledge of general news while possibly also decreasing belief in misinformation circulating online. Third, Facebook deactivation may have reduced self-reported net votes for Trump, though this effect does not meet our preregistered significance threshold. Finally, the effects of both Facebook and Instagram deactivation on affective and issue polarization, perceived legitimacy of the election, candidate favorability, and voter turnout were all precisely estimated and close to zero.

17) Such a great point about what most 20th century historical dramas get wrong, “Everyone in This TV Show Should Be Smoking“

Palm Royalewears its time period like a sweetheart-neckline cocktail dress. From sunglasses and boat shoes to headscarves, wallpaper, and large automobiles, it’s as good a job of material-historical re-creation as you’ll see on television. Every element has been researched, designed, and presented with the utmost care. When Kristen Wiig’s Maxine Dellacorte sits poolside reading the local society pages or Allison Janney’s Evelyn rocks a pair of sunglasses big and bold enough to get filched by Truman Capote, you feel as if you’re looking at a spread from an old magazine in a vintage store that’s come alive. But something’s missing. Something that should complete the panorama as perfectly as a splash of Angostura bitters in a Manhattan cocktail.

Smoke.

Nobody smokes on Palm Royale, which is set in Florida in 1969. This is not right, artistically or historically. According to U.S. government statistics, a little less than half the adult population smoked in the 1960s, and you could do it just about anywhere — on airplanes, in movie theaters, in the obstetrics waiting rooms of hospitals. Until the 1970s, when TV advertising of cigarettes was banned, smoking was extremely common in movies and less common but far from rare on TV (except for crime dramas and talk shows, where everyone smoked like a chimney). I enjoy the heck out of Palm Royale, but half these characters should be smoking. All the time. In restaurants, in bars, in cars, on front stoops and back porches, behind the wheel of their cars.

And by smoking I don’t mean they should take one or two puffs, then stub it out. They should be exhaling roiling cumulus clouds of smoke during casual conversations, lighting up while watching Walter Cronkite and Johnny Carson, extinguishing cigarettes in bedside ashtrays before they go to sleep. If you catch a glimpse of their dreams, there should be smoking in them. Any period piece set between 1800 and 2000 that doesn’t at least occasionally show people smoking cigarettes, pipes, opium, marijuana, hash, or anything else you can light and inhale is a period piece that’s fundamentally compromised. The farther back in the timeline you go, the more the visuals of the piece should be choked with smoke; whether it’s in the foreground or background doesn’t matter.

Mad Men got this right. Righter than any period drama made for TV during the preceding two decades. Just in case you thought all the smoking was an endorsement, the show began with Madison Avenue advertising-wizard Don Draper, a prodigious smoker, pitching a cigarette ad campaign, and ended with a character who’d smoked through all seven seasons dying from lung cancer. The characters on Mad Men also drank casually — at home, at work, in bars — to a far greater extent than people do now. This is a separate but related discussion. Suffice to say that if you were alive for any part of history prior to the turn of the millennium, you know that people participated in self-destructive but visually interesting activities. To quote David Milch, whose work for Deadwood, NYPD Blue, and Hill Street Blues did not lack for depictions of smoking, drinking, and every other sort of vice, “There are times in life when intoxicants are not only permissible but necessary.”

I’ll be even blunter: Unless the year has a 2 in front of it, your frames had better have haze in them. Any film or TV program set in the Before Times that doesn’t show anywhere from a third to half the adult characters smoking is not actually committed to the fiction. And any platform that pressures storytellers to minimize or eliminate smoking from fiction is not merely square but an enemy of art. Again, if it’s set in period, in your mind the entire thing should smell faintly of tobacco.

18) I had some fun with this, “Are You Smarter Than An LLM?”

19) Drum, “Raw data: Public interest in Joe Biden’s age”

Here’s an interesting tidbit. Since the start of the year there have been precisely two short periods when people were interested in Joe Biden’s age:

The first spike came when special counsel Robert Hur made gratuitous remarks about Biden’s age in his classified documents report and spurred a mountain of press coverage. The second spike came when Biden’s State of the Union address made it clear that his age wasn’t a big deal after all. And since then there’s been nothing.

20) Good stuff from Katherine Wu, “How long should a species stay on life support? Decades into their recovery program, black-footed ferrets still don’t have a clear-cut path to leaving the endangered-species list.”

Roughly a century ago, scientists estimate, up to a million black-footed ferrets scampered across the plains of North America; nowadays, just 340 or so of the weasels are left in the wild, fragmented across 18 reintroduction sites. And plague “is their No. 1 nemesis,” Dean Biggins, a grassland ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, told me. If ferrets were facing only habitat destruction or food insecurity, multiplying them in captivity might be enough to replace what nature has lost. But each time conservationists have added ferrets to the landscape, plague has cut down their numbers.

To keep the species from dying out, researchers have deployed just about every tool they have: vaccines and captive breeding, but also insecticides, artificial insemination, and a medley of safeguards for prairie dogs, the weasels’ primary prey. In 2020, black-footed ferrets even became the first endangered animal in North America to be successfully cloned for conservation purposes. Still, those efforts are not enough. Mike Lockhart, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s former black-footed-ferret recovery coordinator, once thought that, this far into the 21st century, ferrets “would be downlisted at least, maybe even recovered,” he told me. But their numbers have been stagnant in the wild for about a decade. Without new funds, technology, or habitat, the population looks doomed to only decline.

Ferrets’ woes are “absolutely our fault,” Biggins told me. Humans imported plague to North America more than a century ago, unleashing it on creatures whose defenses never had the chance to evolve. That single ecological error has proved essentially impossible to undo. Today, black-footed ferrets exist in the wild only because a select few people, including Livieri, have dedicated their lives to them.

21) NYT’s best books since 2000.

22) Arthur Brooks, “How to Be Less Busy and More Happy”

The solution to excessive busyness might seem simple: do less. But that is easier said than done, isn’t it? After all, the overstuffed schedule we have today was built on trying to meet the expectations of others. But we do have research on busyness, which indicates that the real reasons you’re so overbooked might be much more complicated than this. So if you can understand why you end up with too little time and too much to do, that can point you toward strategies for tackling the problem, lowering your stress, and getting happier.

Researchers have learned that well-being involves a “sweet spot” of busyness. As you surely know from experience, having too little discretionary time lowers happiness. But you can also have too much free time, which reduces life satisfaction due to idleness.

Think of a time when a class was way too easy, or when a job left you with too little to do. Being able to goof off might have been fun for a while, but before long, you probably started to lose your mind. In 2021, scholars at the University of Pennsylvania and UCLA calculated the well-being levels of people with different amounts of time to use at their own discretion; the researchers found that the optimal number of free-time hours in a working day was 9.5—more than half of people’s time awake.

Nine and a half hours is probably a lot more than you usually get or ever could get, between staying employed and living up to family obligations. In fact, the average number of discretionary hours found in the data is 1.8. But even if 9.5 hours is unrealistic, this huge difference is probably reflected in your stress levels and may have longer-term health consequences. The World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization estimate that worldwide, in 2016, as a result of working at least 55 hours a week, some 398,000 people died of a stroke and a further 347,000 died from heart disease. So even if you never get near 9.5 hours, increasing discretionary time is the right health and well-being strategy for most people—and probably for you too. So why aren’t more Americans demanding better work-life balance?

One answer is that for most of us, too much discretionary time is scarier than too little, and we overcorrect to avoid it. If we don’t know how to use it, free time can become idleness, which leads to boredom—and humans hate boredom. Typically, when we are under-occupied, a set of brain structures known as the Default Mode Network is activated, with behavioral effects that can be associated with rumination and self-preoccupation.

23) Frank Bruni, “The Most Important Thing I Teach My Students Isn’t on the Syllabus”

I warn my students. At the start of every semester, on the first day of every course, I confess to certain passions and quirks and tell them to be ready: I’m a stickler for correct grammar, spelling and the like, so if they don’t have it in them to care about and patrol for such errors, they probably won’t end up with the grade they’re after. I want to hear everyone’s voice — I tell them that, too — but I don’t want to hear anybody’s voice so often and so loudly that the other voices don’t have a chance.

And I’m going to repeat one phrase more often than any other: “It’s complicated.” They’ll become familiar with that. They may even become bored with it. I’ll sometimes say it when we’re discussing the roots and branches of a social ill, the motivations of public (and private) actors and a whole lot else, and that’s because I’m standing before them not as an ambassador of certainty or a font of unassailable verities but as an emissary of doubt. I want to give them intelligent questions, not final answers. I want to teach them how much they have to learn — and how much they will always have to learn.

I’d been on the faculty of Duke University and delivering that spiel for more than two years before I realized that each component of it was about the same quality: humility. The grammar-and-spelling bit was about surrendering to an established and easily understood way of doing things that eschewed wild individualism in favor of a common mode of communication. It showed respect for tradition, which is a force that binds us, a folding of the self into a greater whole. The voices bit — well, that’s obvious. It’s a reminder that we share the stages of our communities, our countries, our worlds, with many other actors and should conduct ourselves in a manner that recognizes this fact. And “it’s complicated” is a bulwark against arrogance, absolutism, purity, zeal.

I’d also been delivering that spiel for more than two years before I realized that humility is the antidote to grievance.

Recent Comments