1) Good stuff from Garrett Graff on what the government knows about UFO’s

However, I believe the UFO cover-up is about more than state secrets. The government routinely hides information important and meaningless on all manner of subjects, regardless of whether legitimate national-security concerns are involved. Its default position is to stonewall, especially to conceal embarrassing revelations. After reading thousands of pages of government reports, I believe that the government’s uneasiness over its sheer ignorance drives its secrecy. It just doesn’t know very much.

Officials are, at the end of the day, clueless about what a certain portion of UFOs and UAPs actually are, and they don’t like to say so. After all, “I don’t know” is a terribly uncomfortable response for a bureaucracy that spends more than $900 billion a year on homeland security and national defense.

Decades of declassified memos, internal reports, and study projects create the sense that the government doesn’t have satisfying answers for the most perplexing sightings. In internal documents written before the Freedom of Information Act was passed in 1966, officials, who had no sense that ordinary civilians would read their work, admit that they simply lacked credible explanations. In a then-classified 1947 letter that led to the Air Force’s original effort to study these “flying saucer” reports, Lieutenant General Nathan Twining seemed as baffled as anyone, writing that some of the reported craft “lend belief to the possibility that some of the objects are controlled either manually, automatically, or remotely.” Project Sign, as the effort became known, looked at 273 sightings. After a year, it issued a secret report. Although many UFO sightings were either “errors of the human mind and senses” or “conventional aerial objects,” it said, it couldn’t explain all of them. Some sightings were just too weird to rule on one way or another. “Proof of non-existence is equally impossible to obtain unless a reasonable and convincing explanation is determined for each incident,” the Project Sign team wrote.

2) Good stuff on the alleged racial bias in the tests that teachers need to pass to be teachers in New York. Lots of issues to dig into in here. Among them… are the tests actually biased in any way? Why exactly do racial minorities perform so much worse on average than white teachers? What does it mean for a test to be racially biased? Are schools of education doing a good enough job on educating new teachers? Are these tests actually measuring at all what teachers should know?

3) My Thanksgiving plans this week were canceled due to one child, my wife, and me all getting a stomach bug this week. It was mercifully short, but it still sucks. National Geographic on the evolutionary marvel that is norovirus:

Noroviruses are one of virology’s great open secrets. In a recent issue of The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Aron Hall of the Centers for Disease Control declared, “Noroviruses are perhaps the perfect human pathogen.”

Here’s what inspires awe in scientists like Hall.

Each norovirus carries just nine protein-coding genes (you have about 20,000). Even with that skimpy genetic toolkit, noroviruses can break the locks on our cells, slip in, and hack our own DNA to make new noroviruses. The details of this invasion are sketchy, alas, because scientists haven’t figured out a good way to rear noroviruses in human cells in their labs. It’s not even clear exactly which type of cell they invade once they reach the gut. Regardless of the type, they clearly know how to exploit their hosts. Noroviruses come roaring out of the infected cells in vast numbers. And then they come roaring out of the body. Within a day of infection, noroviruses have rewired our digestive system so that stuff comes flying out from both ends.

To trigger diarrhea, the viruses alter the intestinal lining, causing cells to dump out their fluids, which then gets washed out of the body–along with many, many, many noroviruses. Each gram of feces contains around five billion noroviruses. (Yes, billion.)

Noroviruses also make us puke. And if you can gather enough strength to think clearly about this, virus-driven vomit is a pretty remarkable manipulation of a host. Vomiting occurs when our nerves send signals that swiftly contract the muscles lining the stomach. Vomiting does us a lot of good when we’re hurling out some noxious substance that would do us harm. But repeated projectile vomiting of the sort that noroviruses cause serve another function: they let the viruses to find a new host.

To get us to throw up so violently, noroviruses must tap into our nervous systems, but it’s not clear how they do so. Here’s one particularly creepy hint: some studies indicate that during a norovirus infection, our stomachs slow down the passage of food into the intestines. In other words, they seem to load up the stomach in preparation for vomiting. Every particle of that stored food is a potential vehicle for noroviruses when it comes flying out of the mouth.

Once the norovirus emerges from its miserable host, it has to survive in the environment. Noroviruses have no trouble doing so, it seems. Fine droplets released from sick people can float through the air and settle on food, on countertops, in swimming pools. They can survive freezing and heating and cleaning with many chemical disinfectants. In 2010, scientists surveyed a hospital for noroviruses and found 21 different types sitting on a single countertop. It takes fewer than twenty noroviruses slipping into a person’s mouth to start a new infection.

4) My kids (okay, me, too) love the insane-sized Bucee’s convenience stores. Nice article on the newest and biggest ever in the Washington Post.

5) Frustratingly, large-scale interventions to help teen mental health don’t seem to work, “These Teens Got Therapy. Then They Got Worse.: The kids are not all right, and frustratingly, we don’t really know how to help them.”

You have to admit, it seemed like a great way to help anxious and depressed teens.

Researchers in Australia assigned more than 1,000 young teenagers to one of two classes: either a typical middle-school health class or one that taught a version of a mental-health treatment called dialectical behavior therapy, or DBT. After eight weeks, the researchers planned to measure whether the DBT teens’ mental health had improved.

The therapy was based on strong science: DBT incorporates some classic techniques from therapy, such as cognitive reappraisal, or reframing negative events in a more positive way, and it also includes more avant-garde techniques such as mindfulness, the practice of being in the present moment. Both techniques have been proven to alleviate psychological struggles.

This special DBT-for-teens program also covered a range of both mental-health coping strategies and life skills—which are, again, correlated with health and happiness. One week, students were instructed to pay attention to things they wouldn’t typically notice, such as a sunset. Another, they were told to sleep more, eat right, and exercise. They were taught to accept unpleasant things they couldn’t change, and also how to distract themselves from negative emotions and ask for things they need. “We really tried to put the focus on, how can you apply some of this stuff to things that are happening in your everyday lives already?” Lauren Harvey, a psychologist at the University of Sydney and the lead author of the study, told me.

But what happened was not what Harvey and her co-authors predicted. The therapy seemed to make the kids worse. Immediately after the intervention, the therapy group had worse relationships with their parents and increases in depression and anxiety. They were also less emotionally regulated and had less awareness of their emotions, and they reported a lower quality of life, compared with the control group.

Most of these negative effects dissipated after a few months, but six months later, the therapy group was still reporting poorer relationships with their parents.

These results are, well, depressing. Therapy is supposed to relieve depression, not exacerbate it. (And, in case it’s not clear, although it’s disappointing that the therapy program didn’t work, it’s commendable that Harvey and her colleagues analyzed it objectively and published the negative results.)

But for people who study teen-mental-health treatments, these findings are part of a familiar pattern. All sorts of so-called universal interventions, in which a big group of teens are subjected to “healthy” messaging from adults, have failed. Last year, a study of thousands of British kids who were put through a mindfulness program found that, in the end, they had the same depression and well-being outcomes as the control group. A cognitive-behavioral-therapy program for teens had similarly disappointing results—it proved no better than regular classwork.

6) NYT guest essay on the issue:

Why were these programs counterproductive? The WISE Teens researchers suggest, convincingly, that the teenagers weren’t engaged enough in the program and might have felt overwhelmed by having too many tools and skills presented to them without enough time to master them. (The study found that WISE Teens participants who spent more time practicing the skills at home showed some slight mental health benefits — though most of the participants did not engage in home practice.)

But I would venture three additional explanations for the backfiring, all of which dovetail with what other research tells us about youth mental health.

First, by focusing teenagers’ attention on mental health issues, these interventions may have unwittingly exacerbated their problems. Lucy Foulkes, an Oxford psychologist, calls this phenomenon “prevalence inflation” — when greater awareness of mental illness leads people to talk of normal life struggles in terms of “symptoms” and “diagnoses.” These sorts of labels begin to dictate how people view themselves, in ways that can become self-fulfilling.

Teenagers, who are still developing their identities, are especially prone to take psychological labels to heart. Instead of “I am nervous about X,” a teenager might say, “I can’t do X because I have anxiety” — a reframing that research shows undermines resilience by encouraging people to view everyday challenges as insurmountable.

It’s generally a sign of progress when diagnoses that were once whispered in shameful secrecy enter our everyday vocabulary and shed their stigma. But especially online, where therapy “influencers” flood social media feeds with content about trauma, panic attacks and personality disorders, greater awareness of mental health problems risks encouraging self-diagnosis and the pathologizing of commonplace emotions — what Dr. Foulkes calls “problems of living.” When teenagers gravitate toward such content on their social media feeds, algorithms serve them more of it, intensifying the feedback loop.

A second possible explanation for why these programs backfired is that they were provided in the wrong place and to the wrong people. The structure of school, which emphasizes evaluation and achievement, may clash with practicing “slow” contemplative skills like mindfulness. And many of the skills taught in these programs were developed for people coping with severe mental illness, not everyday stresses. These tools might not feel applicable to teenagers who aren’t deeply struggling — and on the flip side, their wide-scale adoption might make them seem too generic and watered-down to teenagers who are truly ill.

A third possible explanation is that these interventions offered enough information to highlight a problem, but not enough to fix it. As research has repeatedly shown, the most effective therapies involve not just learning skills but also developing meaningful relationships. Even the most structured cognitive behavioral approaches recognize the value of a strong working therapeutic alliance between therapist and client. Effective therapies often require clients to do hard things: Exposure therapies for anxiety, for example, ask clients to confront fears they’d prefer to avoid. Such interventions work best with steady, consistent, hands-on support from a dedicated therapist.

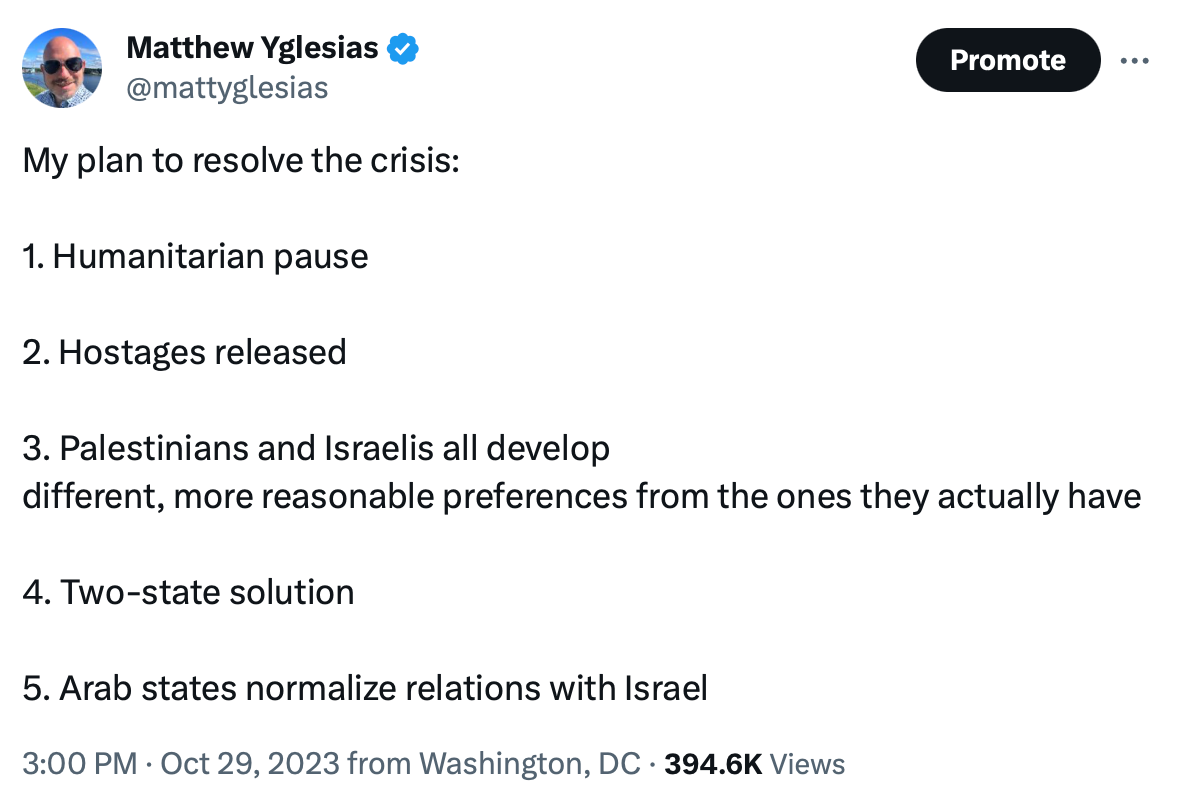

7) Love this from Yglesias. Among all the stuff, we should also talk about how amazing bad Trump is on the issues, “Trump would make inflation worse: It’s better to make things better”

The press still largely covers Trump as an amusing sideshow, as if the world were stuck in a perpetual 2015, and the loudest critiques of this I hear call for more alarmist coverage of his authoritarian leanings. But I think the single most under covered story in American politics is about what you might call the “boring” stakes of the 2024 election. If the country elects Trump and a Republican congress and they implement their ideas on tax policy, trade, and immigration, what’s going to happen to the big economic variables that everyone cares about?

Because it seems to me that either they will make inflation and interest rates a lot higher, or else they’re going to be forced into the kind of draconian Social Security and Medicare cuts they claim not to want.

8) And Brian Beutler, “The 2024 Election Is About Real Things: It’s early still, but public perception of the candidates has lost touch with reality”

A year out from the election, my sense is that the public is horribly underinformed about the election, even having lived through a one-term Trump presidency and almost three years of the Biden administration. And as I see it, the stakes this time around are broadly comparable directionally to the stakes of the 2016 election, but somewhat higher overall.

In 2016 the judiciary was up for grabs, but by now it’s already lost to the GOP. Trump would obviously make the bench even more corrupt and right-wing in a second term, but much of that damage has already been done.

And as a result of that damage, Republican victory in 2024 could easily result in a national ban on abortion. If Biden’s re-elected, by contrast, the status quo will hold; if his party reconsolidates control of Congress, Democrats could even codify the protections of Roe v. Wade across the country.

Unlike in 2016, Republicans probably won’t be running on a defining policy grievance. Biden doesn’t have a signature structural reform under his belt that significantly expands the social safety net or regulatory state. There’s no “Bidencare” for Republicans to say they want to “repeal and replace.”

But there’s a bunch of smaller-bore stuff that’s nevertheless incredibly important, and Republicans are gunning for much of it.

Republicans say they want to repeal an Inflation Reduction Act initiative that’s already making prescription drugs cheaper for seniors, and they’d almost certainly rescind the legislation’s IRS enforcement funds. Cronies would take over regulatory agencies again. Junk fees would be so back.

Just this week, a Trump-appointed appellate judge wrote a lawless opinion, which, if upheld by the Supreme Court, would essentially give the president sole jurisdiction to decide whether anyone has a valid claim of discrimination under the Voting Rights Act, making it a dead letter under Trump. Despite failing to repeal the ACA, Trump managed to temporarily reverse the decrease in the uninsured rate, effectively pushing millions of Americans off of their health plans. He’d do that again.

Matthew Yglesias has been at pains to convey a simple idea: Whatever voters say about whom they trust more to improve “the economy,” the empirical fact is that both candidates have economic agendas, and Trump’s agenda of tariffs and large, regressive tax cuts would cause inflation—now low and falling—to rise again. But for now at least political reporters seem much more interested in what economic-approval polls say than in providing voters the information they need to better align public opinion with reality.

We can’t possibly know what the state of the war between Israel and Hamas will be a year from now, or if there will even be one, but we do know that Trump is more solicitous of the Israeli right wing than Biden (who’s still plenty solicitous), totally indifferent to the plight of Palestine, and embroiled in a corrupt relationship with Benjamin Netanyahu. And the Saudi royal family. And…

In a second Trump administration, the U.S. would probably abandon Ukraine and NATO, and Trump would rampage through the U.S. bureaucracy, driving expertise out of government, purging enemies, encouraging or ordering violence and judicial retribution against them, and generally laying waste to the rule of law.

Some of this stuff would only be possible if one party or another manages to consolidate control of Congress and the White House. But plenty of it is within the discretion of the president alone. And thanks to some of the most undemocratic aspects of our political system, Trump is more likely to enjoy a governing trifecta if he wins than Biden is.

9) Edsall talks to a bunch of experts on Trump’s profoundly warped and dangerous psychology:

I asked Donald R. Lynam, a professor of psychology at Purdue, the same question, and he emailed his reply: “The escalation is quite consistent with grandiose narcissism. Trump is reacting more and more angrily to what he perceives as his unfair treatment and failure to be admired, appreciated and adored in the way that he believes is his due.”

Grandiose narcissists, Lynam continued, “feel they are special and that normal rules don’t apply to them. They require attention and admiration.” He added, “This behavior is also consistent with psychopathy, which is pretty much grandiose narcissism plus poor impulse control.”

Most of the specialists I contacted see Trump’s recent behavior and public comments as part of an evolving process.

“Trump is an aging malignant narcissist,” Aaron L. Pincus, a professor of psychology at Penn State, wrote in an email. “As he ages, he appears to be losing impulse control and is slipping cognitively. So we are seeing a more unfiltered version of his pathology. Quite dangerous.”

In addition, Pincus continued, “Trump seems increasingly paranoid, which can also be a reflection of his aging brain and mental decline.”

The result? “Greater hostility and less ability to reflect on the implications and consequences of his behavior.” …

A recent editorial in The Economist carried the headline “Donald Trump Poses the Biggest Danger to the World in 2024.” “A second Trump term,” the editorial concluded:

would be a watershed in a way the first was not. Victory would confirm his most destructive instincts about power. His plans would encounter less resistance. And because America will have voted him in while knowing the worst, its moral authority would decline. The election will be decided by tens of thousands of voters in just a handful of states. In 2024 the fate of the world will depend on their ballots.

Klaas of University College London concluded that a crucial factor in Trump’s political survival is the failure of the media in this country to recognize that the single most important story in the presidential election, a story that should dominate all others, is the enormous threat Trump poses:

The man who, as president, incited a violent attack on the U.S. Capitol in order to overturn an election is again openly fomenting political violence while explicitly endorsing authoritarian strategies should he return to power. That is the story of the 2024 election. Everything else is just window dressing.

10) This is pretty fascinating. Ethically thorny as hell, but consider me in favor, “When Does Life Stop? A New Way of Harvesting Organs Divides Doctors. The technique restarts circulation after an organ donor is declared dead. But first surgeons cut off blood flow to the brain. One surgeon called it “creepy.” “

A new method for retrieving hearts from organ donors has ignited a debate over the surprisingly blurry line between life and death in a hospital — and whether there is any possibility that donors might still experience some trace of consciousness or pain as their organs are harvested.

The new method has divided major hospitals in New York City and beyond. It has been championed by NYU Langone Health in Manhattan, which says it became the first hospital in the United States in 2020 to try the new method. But NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, which has the city’s largest organ transplant program, has rejected the technique after an ethics committee there examined the issue.

If adopted more widely, the method will significantly increase the number of hearts available for transplantation, saving lives.

The reason is that most heart donors currently come from a small category of deaths: donors who have been declared brain dead, often after a traumatic incident like a car accident. But they remain on life support — their heart beats, and their blood circulates, bringing oxygen to their organs — until a transplant team recovers their organs.

The new technique, transplant surgeons say, significantly expands the potential pool to patients who are comatose but not brain dead, and whose families have withdrawn life support because there is little chance of recovery. After these patients’ hearts stop, they are declared dead. But hearts are almost never recovered from these donors because they are often damaged by oxygen depletion during the dying process.

Surgeons have discovered that returning blood flow to the heart, after the donor has been declared dead, will restore it to a remarkable degree, making it suitable for transplant.

But two aspects of the procedure have left some surgeons and bioethicists uncomfortable.

The first problem, some ethicists and surgeons say, stems from the way death has traditionally been defined: The heart has stopped and circulation of blood has irreversibly ceased. Because the new procedure involves restarting blood flow, critics say it essentially invalidates the earlier declaration of death.

But that may be a minor problem compared to an additional step surgeons take: They use metal clamps to cut blood flow from the revived heart to the donor’s head, to limit blood flow to the brain to prevent the possibility that any brain activity is restored. Some physicians and ethicists say that is a tacit admission that the donor might not be legally dead.

11) Safe to say more than one person really screwed up here, “Animals Meant for Adoption May Have Been Turned Into Reptile Food: The fate of more than 250 rabbits, guinea pigs and rats remains unknown more than three months after they were sent to a humane society in Arizona.”

12) Loved reading Noah Smith on how Ireland got so rich. I’ve never had a particular interest in development economics, but, Smith’s explanations are always so fascinating.

13) People hate inflation because it never comes back to where it was, it just slows down. I’m never paying $3.75 for generic rising crust pizzas again (yes, that is an item I personally track). What people seem to want is deflation, but that’s bad.

14) It’s definitely frustrating that so many people still die of Tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis, which is preventable and curable, has reclaimed the title of the world’s leading infectious disease killer, after being supplanted from its long reign by Covid-19. But worldwide, 40 percent of people who are living with TB are untreated and undiagnosed, according to the World Health Organization. The disease killed 1.36 million people in 2022, according to a new W.H.O. report released on Tuesday.

The numbers are all the more troubling because this is a moment of great hope in the fight against TB: Significant innovations in diagnosing and treating it have started to reach developing countries, and clinical trial results show promise for a new vaccine. Infectious disease experts who have battled TB for decades express a new conviction that, with enough money and a commitment to bring those tools to neglected communities, TB could be nearly vanquished…

Those diagnosed with drug-resistant TB receive medication to take for six months — a far shorter time than previously required. For decades, the standard treatment for drug-resistant TB was to take drugs daily for a year and a half, sometimes two years. Inevitably, many patients stopped taking the medicines before they were cured and ended up with more severe disease. The new drugs have far fewer onerous side effects than older medications, which could cause permanent deafness and psychiatric disorders. Such improvements help more people to continue taking the drugs, which is good for patients, and eases the strain on a fragile health system.

In Ghana and most other countries with a high prevalence of TB, the drugs are paid for by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, an international partnership that raises money to help countries fight the diseases. The sustainability of those programs depends on donor largess. Currently, the treatment for adults recommended by the W.H.O. costs at least $150 per patient in low- and middle-income countries.

“If our patients had to pay, we would not have one single person taking treatment,” Ms. Yahaya said.

Still, there has been progress in recent months in making the medicines more affordable, and prices may soon drop further. Johnson & Johnson has lowered the price of a key TB drug in some developing countries. The company had faced pressure from patient advocacy groups, the United Nations and even the novelist John Green, who devoted his widely followed TikTok account to TB test and treatment prices. The company also agreed in September not to enforce a patent, which means generic drug companies in India and elsewhere will be able to make a significantly cheaper version of the medication.

15) This is pretty cool, “A Giant Leap for the Leap Second. Is Humankind Ready? A top scientist has proposed a new way to reconcile the two different ways that our clocks keep time. Meet — wait for it — the leap minute.”

Later this month, delegations from around the world will head to a conference in Dubai to discuss international treaties involving radio frequencies, satellite coordination and other tricky technical issues. These include the nagging problem of the clocks.

For 50 years, the international community has carefully and precariously balanced two different ways of keeping time. One method, based on Earth’s rotation, is as old as human timekeeping itself, an ancient and common-sense reliance on the position of the sun and stars. The other, more precise method coaxes a steady, reliable frequency from the changing state of cesium atoms and provides essential regularity for the digital devices that dominate our lives.

The trouble is that the times on these clocks diverge. The astronomical time, called Universal Time, or UT1, has tended to fall a few clicks behind the atomic one, called International Atomic Time, or TAI. So every few years since 1972, the two times have been synced by the insertion of leap seconds — pausing the atomic clocks briefly to let the astronomic one catch up. This creates UTC, Coordinated Universal Time.

But it’s hard to forecast precisely when the leap second will be required, and this has created an intensifying headache for technology companies, countries and the world’s timekeepers.

“Having to deal with leap seconds drives me crazy,” said Judah Levine, head of the Network Synchronization Project in the Time and Frequency Division at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, or NIST, in Boulder, Colo., where he is a leading thinker on coordinating the world’s clocks. He is constantly badgered for updates and better solutions, he said: “I get a bazillion emails.”

On the eve of the next international discussion, Dr. Levine has written a paper that proposes a new solution: the leap minute. The idea is to sync the clocks less frequently, perhaps every half-century, essentially letting atomic time diverge from cosmos-based time for 60 seconds or even a tad longer, and basically forgetting about it in the meantime.

“We all need to relax a little bit,” Dr. Levine said.

16) I enjoyed Yglesias‘ “Grand theory of the left” earlier this month:

As progressive ideas have grown in prominence and influence, it’s become much harder to ignore the more extreme versions of progressive ideas.

My general view, though, is that most political tendencies come in both sound and unsound forms. In college, I learned a lot from Robert Nozick, who introduced me to some important libertarian ideas, and over the years I’ve learned a lot about different policy issues from friends and acquaintances at libertarian institutions like Cato and Mercatus. Given the populist climate of Trump-era politics, I think libertarianism is kind of underrated and deserves more influence. That being said, precisely because libertarian ideas have such a clear grounding in a small number of principles, I think they tend to morph with alarming speed into wildly unsound versions of themselves.

This country could benefit from a lot of supply-side health care policy reforms that are mostly deregulatory and market-oriented in nature. But overly lax opioid prescribing policies have been disastrous, and aversion to paternalistic public health measures has contributed heavily to America’s anomalously poor life expectancy outcomes. We also really do not need a true market-based approach to health care financing where anyone poor who gets sick just dies in the street without treatment.

By the same token, though, most bad trends on the left are recognizable versions of perfectly reasonable ideas. It is true that burning fossil fuels has negative externalities and that public policy should do more to curb those externalities. There is real evidence of racial bias in traffic stops and a problematic tendency for conservatives to endorse or justify racially biased policies in terms of statistical aggregates. The government of Israel really has been trying to steal the West Bank, in parallel with its more legitimate security policies, and right-wing politicians in both Israel and the United States express troubling and borderline genocidal attitudes toward Palestinian civilians. Left Covid maximalism went off the rails, but the basic idea that “Donald Trump should take the pandemic more seriously” was completely correct — countless lives could have been saved if he’d urged his fans to skip holiday travel in November-January 2020 and just wait for the vaccine rollout. Basically anything can be taken too far, and in a big world, someone is going to try…

The leftward shift means that the balance of power between unsound right-wing ideas and unsound left-wing ideas is in closer equilibrium today than it was in 1998. That’s change for the better, all things considered. But it does mean that paying attention to and pushing back on unsound left-wing ideas is more important than it used to be, because the odds that such ideas will have meaningful policy influence are higher. The important thing, though, isn’t to deconstruct some big picture construct, it’s to plug away on the specifics, day-in and day-out. The strong and slow boring of hard boards, so to speak.

17) Thanks to BB for this, “Supercentenarian and remarkable age records exhibit patterns indicative of clerical errors and pension fraud”

The observation of individuals attaining remarkable ages, and their concentration into geographic sub-regions or ‘blue zones’, has generated considerable scientific interest. Proposed drivers of remarkable longevity include high vegetable intake, strong social connections, and genetic markers. Here, we reveal new predictors of remarkable longevity and ‘supercentenarian’ status. In the United States supercentenarian status is predicted by the absence of vital registration. In the UK, Italy, Japan, and France remarkable longevity is instead predicted by regional poverty, old-age poverty, material deprivation, low incomes, high crime rates, a remote region of birth, worse health, and fewer 90+ year old people. In addition, supercentenarian birthdates are concentrated on the first of the month and days divisible by five: patterns indicative of widespread fraud and error. As such, relative poverty and missing vital documents constitute unexpected predictors of centenarian and supercentenarian status, and support a primary role of fraud and error in generating remarkable human age records.

18) I love that medical science is always learning new things, even low tech, that can save lives,

Shortly after a baby is born, doctors clamp the umbilical cord linking the infant to the placenta, which is still inside the mother’s uterus, and then cut it. New research shows that if doctors wait at least two minutes after the birth to clamp the cord, they significantly improve in-hospital survival rates for premature infants.

Delayed cord clamping — an intervention that can be introduced at relatively little cost — is believed to help because it allows umbilical cord blood, which is rich in iron, stem cells and antibodies, to flow back to the baby. Some experts say that it’s not entirely clear why the strategy seems to help, but that the data is convincing.

19) America is unusual in our reliance on 30-year mortgages. And it’s not great:

Buying a home was hard before the pandemic. Somehow, it keeps getting harder.

Prices, already sky-high, have gotten even higher, up nearly 40 percent over the past three years. Available homes have gotten scarcer: Listings are down nearly 20 percent over the same period. And now interest rates have soared to a 20-year high, eroding buying power without — in defiance of normal economic logic — doing much to dent prices.

None of which, of course, is a problem for people who already own homes. They have been insulated from rising interest rates and, to a degree, from rising consumer prices. Their homes are worth more than ever. Their monthly housing costs are, for the most part, locked in place.

The reason for that divide — a big part of it, anyway — is a unique, ubiquitous feature of the U.S. housing market: the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage.

That mortgage has been so common for so long that it can be easy to forget how strange it is. Because the interest rate is fixed, homeowners get to freeze their monthly loan payments for as much as three decades, even if inflation picks up or interest rates rise. But because most U.S. mortgages can be paid off early with no penalty, homeowners can simply refinance if rates go down. Buyers get all of the benefits of a fixed rate, with none of the risks.

“It’s a one-sided bet,” said John Y. Campbell, a Harvard economist who has argued that the 30-year mortgage contributes to inequality. “If inflation goes way up, the lenders lose and the borrowers win. Whereas if inflation goes down, the borrower just refinances.”

This isn’t how things work elsewhere in the world. In Britain and Canada, among other places, interest rates are generally fixed for only a few years. That means the pain of higher rates is spread more evenly between buyers and existing owners.

In other countries, such as Germany, fixed-rate mortgages are common but borrowers can’t easily refinance. That means new buyers are dealing with higher borrowing costs, but so are longtime owners who bought when rates were higher. (Denmark has a system comparable to the United States’, but down payments are generally larger and lending standards stricter.)

Only the United States has such an extreme system of winners and losers, in which new buyers face borrowing costs of 7.5 percent or more while two-thirds of existing mortgage holders pay less than 4 percent. On a $400,000 home, that’s a difference of $1,000 in monthly housing costs.

“It’s a bifurcated market,” said Selma Hepp, chief economist at the real estate site CoreLogic. “It’s a market of haves and have-nots.”

20) And an excellent piece from Brian Klaas to finish things off, “The Biggest Hidden Bias in Politics”

Happy almost Thanksgiving to all you American readers! May it be restful and relaxing, full of good food and good cheer, with plenty of toasts for everything to be thankful for this year.

However, many of you will be dreading a difficult aspect of Thanksgiving in modern America: how do you get through the meal when one (or more) of your crazy relatives believes the moon landing was faked, that the Denver airport is the secret headquarters of the Illuminati, and that the only reason you’re not clever enough to recognize these hidden truths is because of the brainwave interference you’re crippled with forever due to the 5G chip that came as a Trojan Horse inside the covid “vaccines.”

Such difficult family dynamics function as an alarming mirror for American society, which, to a greater extent than other rich democracies, is plagued by delusional, conspiratorial politics. That poses a serious, urgent puzzle: why is the United States such an outlier for unhinged political extremism that’s utterly detached from reality?

To answer that question, let’s start with a seemingly unrelated pop quiz: how many of you can correctly identify who is pictured in the photograph below?

The correct answer is Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India, leader of a country that is home to nearly 1 out of every 5 people on the planet. He’s one of the most important people in the world—and, by appearance and dress, one of the most recognizable. So, when Americans were asked to identify an array of photographs of prominent figures from politics, business, celebrities, you name it, what percentage of Americans could identify Modi correctly?

The answer: 3 percent. Three percent.

Let’s put that into perspective. Sixteen percent of Americans could recognize the face of PewDiePie, the Swedish YouTuber, which was pretty close to the proportion of Americans who correctly identified the face of Xi Jinping, the President of China (20 percent).

There is a clear trend in the data: most Americans can’t identify prominent world leaders, including some of their own—but have no trouble with celebrities. Take a look at the percentage of Americans who correctly identified the following people in this 2019 New York Times quiz:

-

Narendra Modi (3 percent)

-

Xi Jinping (20 percent)

-

Boris Johnson (20 percent)

-

Mitch McConnell (35 percent)

-

Vladimir Putin (60 percent)

-

Justin Bieber (67 percent)

-

The Rock (85 percent)

-

Oprah (86 percent)

These figures are reflective of the biggest hidden bias in politics—what I call Ignorance Bias.

We focus so much energy on how the news is reported that we don’t pause to consider how few people actually consume it, or how little of it on the airwaves is about governance rather than political gossip and horserace-style fanfare.

Even Fox & Friends, which usually has the biggest share of the cable TV morning show market, averages around 1.2 million viewers. That’s 0.36 percent of the US population. One out of every 275 Americans is watching. (Even if you don’t include children in these figures, it’s still a tiny slice of the adult population).

It’s a bit like if the Titanic lookouts got consumed in a debate over whether the tip of the iceberg slanted to the left or the right, all while they slammed into the enormous, but much more dangerous bit lurking below the surface. The disconcerting truth is this: The biggest bias in (mis)understanding politics is the bias that political elites assume most other people think about politics often and have a basic working knowledge of it that is rooted in facts and reality.

That’s not a safe assumption.

One recent survey found that 52 percent of Americans can’t name a single US Supreme Court Justice. In 2011, a poll found that twice as many Americans knew that Randy Jackson was a judge on American Idol than could correctly identify the Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court. And in 2006, three years after the war in Iraq began—the most important element of US foreign policy at the time—six in ten Americans couldn’t identify Iraq on a map of the Middle East. (A little over half could point to New York state on a map).

Here’s a map, from the New York Times, of thousands of Americans trying to put a dot on North Korea. It’s a pretty random spread.

Most discussions of these astonishing revelations lead only to condemnation and calls for education. And while I agree that educational investments form the long-term cornerstone of democratic success, it’s worth more carefully exploring the more immediate political implications of the fact that vast swaths of the voting public don’t have basic information about the political world or how our governments operate.

Recent Comments